Ningún lugar

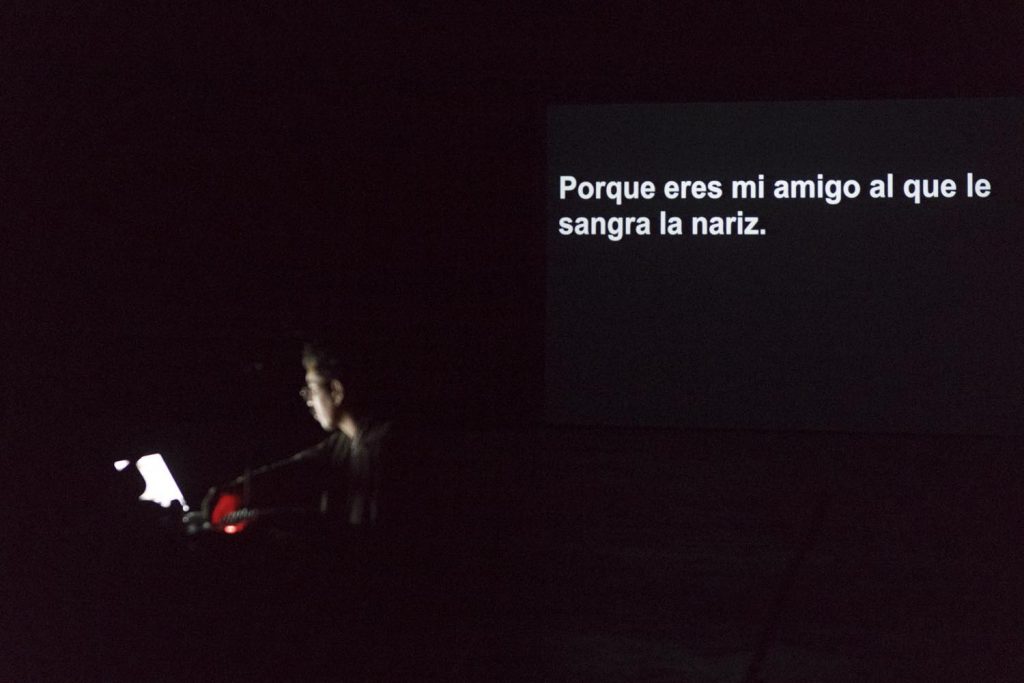

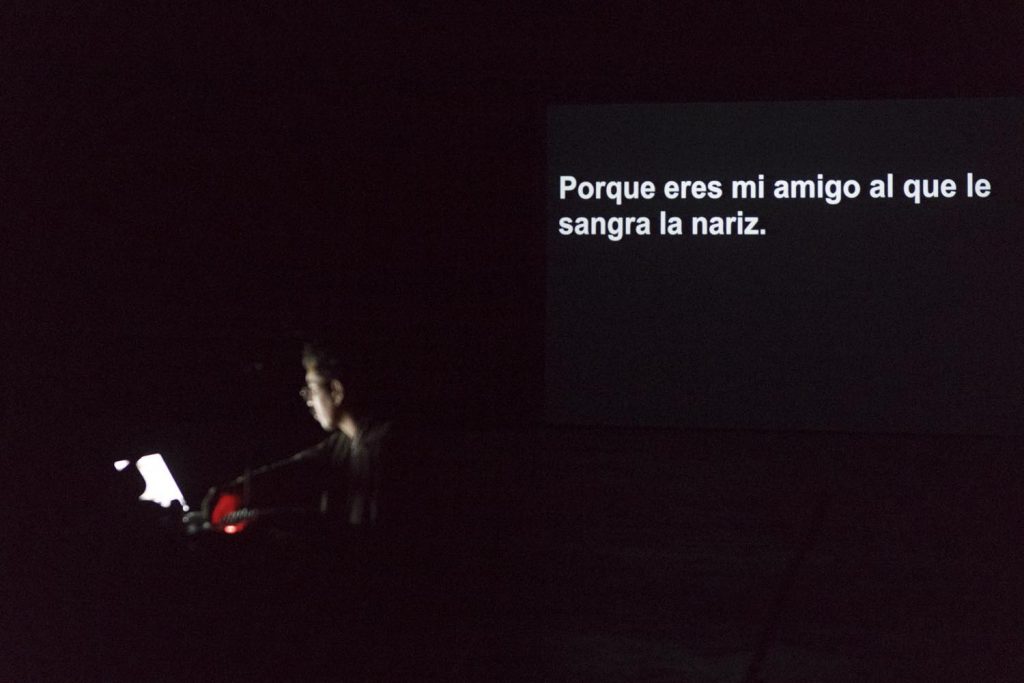

Performance, 90 minutos.

Naves Matadero Centro Internacional de Artes Vivas, Madrid. 21 to 24 September 2017.

Festival Sâlmon, Mercat de les flors, Barcelona. 9 February 2019.

“Undated, 1950

I walk down the street. With nowhere to go. I stop to look at the billboards, the shop windows. I look at the price tags on the brims of hats. Do I need a hat? Perhaps I should buy one. No. Maybe next time. I’ve got time to spare.

I cross the street and go back towards Broadway. The Broadway of cinemas, theatres, second-hand shops, slums.

I have absolutely nowhere to go, nowhere to run. When one has gone such a long distance, it no longer matters if he is here or there, or for how many hours he’s walked. In ten years I might find myself in a completely different place, who knows, and it doesn’t matter one bit. Once you leave home, you’re never at home again.“ Jonas Mekas, I Had Nowhere to Go

In the book I Had Nowhere to Go avant-garde Lithuanian filmmaker Jonas Mekas tells the story of his exile across war-torn Europe to New York, where he must start his life over again.

Meanwhile, while Mekas walks the streets alone, Nowhere begins, a performance in which his texts and work are taken up by an amateur theatre troupe consisting of Romanian women, a Colombian musician who plays electro cumbia and noise, domestic videos and heaps of junk, in order to build an everyday opera that celebrates life.

Credits

Idea and direction: Nilo Gallego and Chus Domínguez

Collaborative creation and performers: Luminita Moissi, Mirela Ivan, Angelica Simona Enache, Mariana Enache, Julian Mayorga and Claudia Ramos.

Music: Julián Mayorga

Lights: Oscar Villegas

Feauring the special collaboration of: Grupo de Teatro Equivalientes (Tetuán), Raquel Sanchez, Serrín (Raul Alaejos and Ana Cortés)

Thanks to: Biblioteca Musical Víctor Espinós, Alberto Nanclares, Iván Pérez, Filmadrid and Sebastian Mekas

Special thanks to Jonas Mekas

Texts loosely adapted from the books, films and video diaries of Jonas Mekas

Language: Spanish, Romanian

Nowhere (Text by María Salgado published in her blog Globo rápido).

Yesterday I went to see Nowhere by Nilo Gallego and Chus Domínguez, and also by Luminita Moissi, Mirela Ivan, Angelica Simona Enache, Mariana Enache, Julián Mayorga, Jonas Mekas, Claudia Ramos, Raúl Alejos, Ana Cortés and Óscar Villegas. This work, in my opinion, is from all of them, each one is different, and this parity is just one of the many wonders of this theater piece. I could not like it more, I burst into tears, but they weren’t tears of grief but of pure joy and delight at the image of exiles, migrations and difficult worlds lived with real flesh and blood through singing and even laughter. I really liked the fact that the beautiful promises that Jonas Mekas made on the video from 11/7/2017 (“the small, the small, the personal”, spoken as he did, with a trembling but firm voice) were all fulfilled. And also that his authorship did not command or impose itself as the most important one on stage: the simple phrases of his diary from exile opened in a historical time (the Second World War) continuing on to the present of migrations brought by the phrases of the performers on stage. There was no importance given to the author’s name. The selected fragments from the newspaper talked about their refusal to go to the army in America because they’d fled Europe as “animals flee” from the war. They also talk about the nose bleeding while crossing the continent at war; about not wanting to work on Saturdays in a factory, and about snow in NYC. And then, a gate opens at the back of the scene, and it snows in Madriz. The snow is everywhere. Magic. I really liked the way the four actresses on stage sang, played and cooked, fearlessly, no imposition, no gesture detached from their presence. The experience of spending more than half of this piece without understanding their language (Romanian), and the moment (WONDERFUL: the best I’ve ever experienced in my life on stage in terms of verbal form) in which they change to the shared language, Spanish-Castilian, because Julián Mayorga (Colombian) and Claudia Ramos (from her accent she seems to be from the peninsula) were sitting at the table.

The verb tenses were all over the place giving a liveliness to their speech, the way of saying, with full communication and many incredibly precise details. Green paper, white paper, small paper and large paper are different versions of the NIE (Foreigner Identity Number), that you could get in a place called Padre Piquer: if any Spanish-speaker is able to understand it better than anyone who does not speak the language, this person would lie. These words seem to mean specific things but the real meaning comes from the ones who use them and do not have the nationality.

I really liked the music, the way Julián Mayorga interrupted the songs to explain things about them. Things such as the meaning of Tolima, or the difference between the European waltz, which traveled to America, and its American version: the pasillo. I was very pleased to see the display on the ground and the collection of each object in a truck with metal pieces that were for sale and other pieces from the world (a cardboard head, a dog, an accordion, traffic signs). I was neither bored nor amused, I just looked on with pleasure, I was very comfortable with and in this work.

I still feel the joy and emotion I felt when leaving: these were very real because the transmission itself was very real. No show, no abuse, misuse or use of others by others (directors for example). No hierarchy, no money. The courage to stage material that could have been manipulated in a thousand ways; the success of each subject in action, including the spectator, will maintain its Agent, that is, its ability to think (the language) and act, in its own way, individually and together (as the language is more or less from all of them when the domain is removed). In short, I can’t explain, what goodness, beauty and justice. Holy crap! It is a must-see!

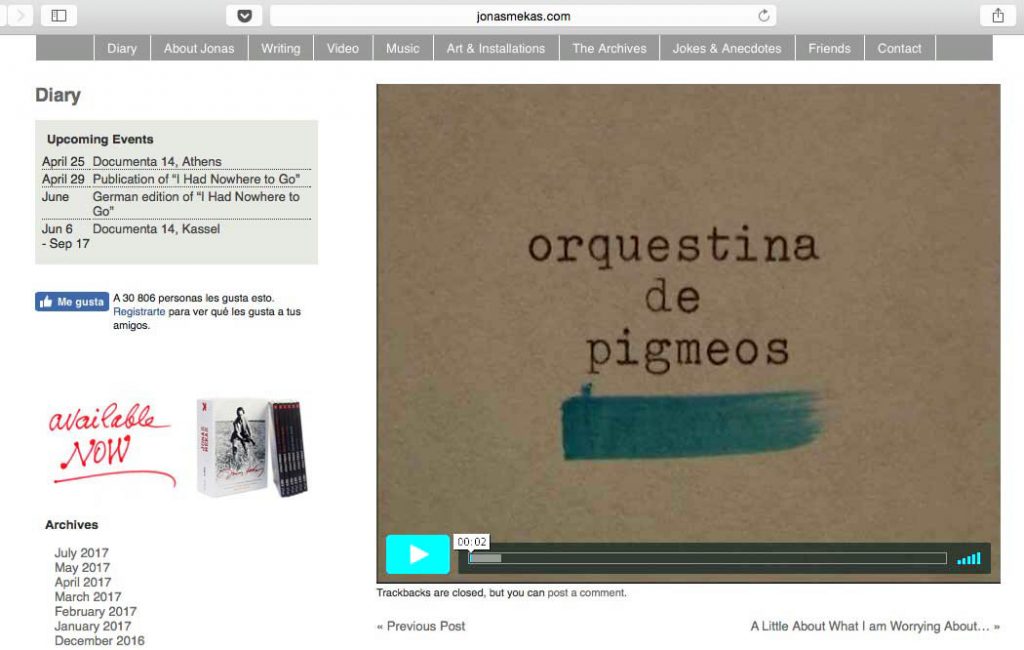

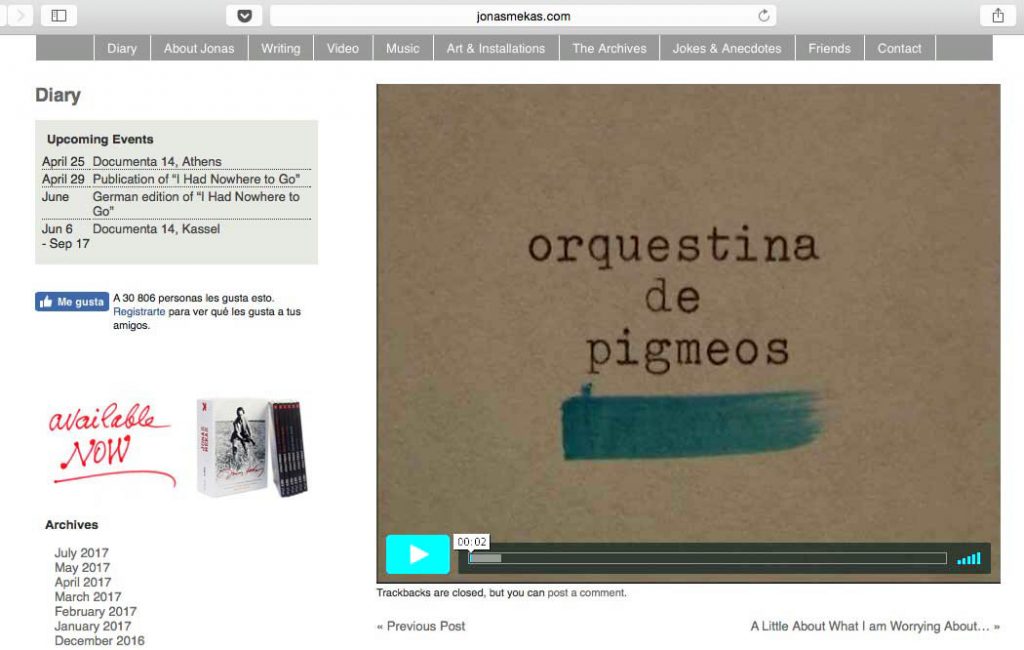

Orquestina de Pigmeos (Text by Rubén Ramos Nogueira and published in Ajo Blanco magazine).

Jonas Mekas is a prestigious Lithuanian filmmaker based in New York. He is 94 years old but, despite his age, he retains an enormous vitality. He is very well-known. Many of us admire him. He has seen a lot of things in his long life. He has met a lot of artists. Mekas has a video diary that he updates from time to time. This summer, he surprised us by publishing a video in which he talked about his recent trip to Europe as a guest of the Documenta Kassel. He said in the video that he had been in big cities, in big events and that he had seen very big things. And that he was tired of everything being so big, too big. But he also said that, fortunately, almost by chance, when passing through Madrid, he had the opportunity to see a rehearsal of Nowhere. It is created by the musician Nilo Gallego and the audiovisual artist-filmmaker Chus Domínguez, who both head Orquestina de Pigmeos, and was premiered at the end of September in the warehouses of the Matadero (the former abattoir). Appearing on stage are a group of non-professional Romanian actresses (Luminita Moissi, Mirela Ivan, Angelica Simona Enache, Mariana Enache), along with the Colombian musician, Julián Mayorga, and Claudia Ramos. There is also another handful of people in the rear (Óscar Villegas, Raquel Sánchez, Raúl Alaejos and Ana Cortés).

There are always a lot of people, because that’s how the Orquestina de Pigmeos works, with a lot of people. In recent years, this has become unusual in the unofficial live art scene (I do not know how to name it anymore). In recent years, this scene has been transforming the old concept of the company so much as to almost destroy it. It is more like a constellation of isolated individuals -probably because of financial reasons- but also because of certain individualistic trends that are possibly being reversed again, who knows? But we were with Mekas. Jonas Mekas, in his videoblog. He is visibly moved. He tells the world that this rehearsal by Orquestina de Pigmeos is the best he has seen, at least in the past year. And he adds: this is what art is all about. OK, perhaps Mekas felt flattered because in the show Orquestina makes good use of his book, I had nowhere to go in which he writes about his exile through war-torn Europe until his arrival in New York. Orquestina de Pigmeos projected the texts which overlap with what occurs on stage. This allows us to contemplate pure life, and also pure artifice (so we can to return again to a hygienic view of life, one that is indistinguishable from the fiction in which we are increasingly immersed), created by people who, like Mekas, also left their countries of origin to reach Madrid. But in the video, Jonas Mekas explains to the world what art is for him. The art that interests him. It’s a definition that gives me goose bumps: it’s simple, straight, small, personal, unpretentious, down-to-earth, connected to life. Something like that, says Mekas. And after many laps of the track, Jonas Mekas found it in a rehearsal of the Orquestina de Pigmeos on a hot summer afternoon in Madrid. I can’t think of better words than the ones Mekas uses to talk about any of the wonderful works that nurture the long history of the Orquestina de Pigmeos. They are the perfect representatives of all those people who have been doing amazing things in the strange territory of arts where, so far, no one has paid attention to them. I find it grossly hypocritical when I listen to many of the promoters of the political change talking about art and culture as the engine for change, while their actions and those of their allies, reveal the great betrayal they are perpetrating. We are missing out on a great opportunity. They can’t know what they are talking about, surely. But it would be so easy to do otherwise. All they have to do is pay close attention to the words of Jonas Mekas and the actions of his friends

Everyone on the ground (Text by Fernando Gandasegui, published in Tea-tron)

Even the flesh is not burning anymore.

The eyes, where are the eyes?

I want to see them.

Tell me,

don’t turn away.

I want to see inside them.

Jonas Mekas. A Requiem for the twentieth century.

If it is true that we live in “interesting times”, as a Chinese might curse someone he hates, it could be that the most obvious symptom is the inverse correlation between the radical readiness of freedom to create, to accumulate and move capital and the gradual loss of all other freedoms; above all, the most severe case, the ones connected to the displacement of people in the world that capital itself has shaped.

Given that there is no place for internal exiles, new wars force new expatriates to seek refuge in what Carlos Fernández Liria called “a kind of inverted Auschwitz”. “The international economic system is an external gas chamber” in today’s concentration camps, there is Nowhere to go for the stateless millions who await a welcome, should they ever arrive. Well, let them wait, -either there or at the bottom of the sea- that will solve the problem. Meanwhile, as usual, there is life, there are lives. As a case in point, Spain (in the worst sense) has failed, without a murmur of complaint, and there are 15,449 refugees who need to be housed.

15,449 lives rejected by a criminal state. Again, it is “the price of freedom”, the FAES (Foundation for Social Studies and Analysis) utters without qualms.

Ningún lugar (Nowhere) by the Orquestina de Pigmeos (The Pygmies’ Orchestra), has the story of the Lithuanian filmmaker Jonas Mekas beating at its heart. And deeper still is its need to be told. The backdrop: the massacre that follows the massacre, the great exile of the twentieth century. There are different wars and criminals today but the consequences are repeated and artists like Nilo Gallego and Chus Domínguez have the same need to explain life from life itself, which again is forced to be reconstructed in displacement, Nowhere. These are stories that not only traverse Syria, Mexico or Burma, these are lives that, when we open our eyes, are around every corner. In this case, they are in Madrid, in the Tetuán neighbourhood, or also in a theatre where the Orquestina de Pigmeos invites us not to look back but to look inside. Let’s see if it burns. Let’s just see.

Everything resulted from chance and also from curiosity.

Jonas Mekas, I had nowhere to go.

The Orquestina de Pigmeos is understood to be “an experimental group dedicated to site-specific intervention”. Whether it is a river, a museum, a factory, a mountain or a theatre and involving working with the locals, the projects that are initially led by Nilo Gallego and Chus Domínguez end up involving dance bands, audience and the spaces created for each occasion. For example, between cigarettes and mosquitoes, strolling along the banks of the Mondego River, a director of Citemor explained with a half-smile how the Orquestina managed to mobilise an entire town for Pigmeus do Mondego (one of the works he remembers best from the 39th editions of the festival).

Almost everything that Nilo Gallego covers–which is almost everything- establishes a particular bond with music, extending the term and including others, blending and unleashing fireworks, is what Chus Domínguez does with cinematography. Together, they lead us to unsuspected, playful, contemplative performativities, showing us the red button, usually in spaces that are not (conventional) stages, although the pair have had long and deep connections with the stage, especially with dance. A Madrid-style dance with “relaxed, unsyncopated rhythms”, an improvised dance that will survive us, will outdance us, and that transpires in the actions of pygmies. A dance, or choreography, that is none other than a form of reading or writing, of composing, language and linguistics, or in the case of Nilo and Chus: “langue”, Saussure’s parole. That’s why they are alive. Now, paradoxes, or para-donkeys, as a professor said after a stroke, they are called to work in theatres, perhaps ironically the setting that is the least “conventional” for this band. And, another exception, with commissions for works of the type that have to be repeated one night after another. Nowhere is a new challenge for the Orquestina de Pigmeos, which this time comprises on stage: Luminita Moissi, Mirela Ivan, Angelica Enache, Mariana Enache, Julián Mayorga and Claudia Ramos.

Stop working! Stop! (…)

Let everything stop.

Let the snakes and the tigers come,

and let them multiply.

Let the grass grow over everything.

Jonas Mekas, I had nowhere to go

After a short while, the girl sitting beside me asks her father: “Will it always be like this?” Nowhere starts with the twilight that filters through Hall 11 of the Matadero, the erstwhile Madrid abattoir, and nothing else. There is no artifice. Now we can start. Mirela emerges from the background with a violin in her hand and walks around the empty space. Is this Butoh, we wonder? She stands in front of the 400 seats and, just like in Herzog’s interludes where a child plays the violin, bows the strings while the orchestra introduces a world that, as it is a piece of music, brings us its themes in the overture. There’s no tuning, appropriately. We keep time together. So near, so far. Density and simultaneity, you choose. Get bored with me, Daddy. I remind you that there is an outside. In this way, we enter the unstable equilibrium of a work that resists the paradox of resisting the conventions of a work. It’s playing at looking fragile, supposedly made of what is happening, but in reality it has sized the theatrical engine up perfectly. And it shows valour in taking the unmeasurable risk of heating and heating and heating the stage to see if it bursts into flames. And it burns. Some of us snap, as the well-bowed string sometimes does. The girl, after falling asleep several times, ends up shouting enthusiastically about the work to her father.

Luminita, Angelica, Mariana, Julián and Claudia emerge. Claudia, as if she were the stage manager, the visible prompter with wireless headphones, will strut from one side to the other for the whole performance, looking as if something is missing, as if anything could happen. Shouldn’t it always be like that? Apart from her warmth, her character strips away any illusionist architecture, giving us room to think that, from the booth, they could do some real-time composing and polishing. Luminita, Angelica and Mariana start to fill the space, which previously was just space, with objects of all kinds. In Nowhere this action is sustained; it could seem as if it were a parody of certain self-absorbed performative practices, but in reality it will draw the arc of the work: the displacement of objects that operate as an infra-slight leitmotiv, as everything on stage repeatedly has ceaseless meaning and often, without us realising, these are loaded with meanings for an hour and a half until, bang! at the end they explode in all directions.

After the overture, the quartet sit down to smoke and don’t stop, like the white sect from the Guilty Remnant in Leftovers. But they are fake cigarettes, a Brechtian knock-on effect of the anti-tobacco law. It is a metaphor of what the theatre usually is. Julián, meanwhile, has already set up. He is very close to the audience and he goes to one side, light and forceful, intervening and accompanying. If someone once said that to make movies all you need is a pencil, maybe now to make music, all you need is a table. Then Julián starts with Old Tolima, a story of loss and displacement. It comes from the peasantry of Colombia, from where he comes and has left. Julián stops and explains the song, in case someone missed out on the meaning. This distancing is reversed with a handling of the intensities over the course of a work which ends with our emotional rendition. “They took the ranch and the cows away from me, and although they weren’t many, they belonged to me, how I miss you, old Tolima, how I would like to go back there”, the gentle song of a musician who is starting to gain traction in Madrid. It is his first time in a theatre for a job that momentarily sustains him in parallel in his intermezzi by Spinetta or Talking Heads.

Nowhere is created in the dramaturgy of density and simultaneity, in the multiplicity of foci and the accumulation of signs. The action on stage coexists with two screens at the end of the warehouse that support performativities. On the left, vertically, we are exposed to videos. On the right, horizontally, are the writings of Jonas Mekas. An image/text that opens Nowhere outwards, hiding the final surprise within. The videos recorded with a mobile phone show us the streets, the houses, the families, the little Romania of Luminita, Mirela, Angelica and Mariana. These scenes were recorded by them, and they invite us, on a subjective level, to enter their lives, the protagonists of Nowhere. The lives that fill every one of Hall 11’s cubic metres, which number quite a few. Four women who become immense at all levels of the work. The one thing we might miss is for conventions to be broken altogether, enabling us to go down to dance and share what they have been cooking in a steaming pot with a real smell, getting inside, the metonymy for what happens in Nowhere until they serve us the Grand Finale.

Life goes on.

Horrible things are happening around us,

and the only way of not going really insane …

because if you start to think about it and feel guilty

for being happy and celebrating everything that happens around you

when all those terrible things are happening …

So I took my camera and I film,

and I celebrate the only thing I see and that I find beautiful right now:

the snow.

Let me be with the snow.

Jonas Mekas, Letter to José Luis Guerín.

At the end, the door at the back of the hall opens, and with it, literally and in every sense, the theatre opens onto the street, from where it should never have left perhaps, the street being the world in any of its forms. The Orquestina de Pigmeos achieve what hardly ever happens: they put the street back into the theatre. “Ground. Nothing more/Ground. Nothing less”, Salinas. The work is baroque, just as the cardboard dog in Las Meninas who has been watching us all the time is baroque. Outside, the passers-by stop and watch us sitting in our seats, spectators of another work, a synecdoche Nowhere, and the Orquestina does a 2 for the price of 1. Between the theatre and the street, or the other way around, it doesn’t matter. Two worlds are joined by poetic license, or not, the snow. It’s snowing and we let it happen. A truck enters the stage and the women gather up all the objects; these are now charged symbols. This transforms the “work” into work, and although some might feel uncomfortable at the stereotypes implied by the scene, it allows us to conjugate the verb “politicise”, as suggested by López Petit, instead of talking about politics or the political. Meanwhile, Julián lacerates Psycho Killer by Talking Heads, the full truck leaves the empty theatre, the door closes, and we stop seeing the snow. Then the girl next to me, now on her feet, shouts to her father: “Don’t close it, don’t close it!”

Direct link here to Jonas Mekas video-diary talking about Ningún lugar: “ (you can also click on the image).

Español

Español